Oshkosh food pantry meeting needs despite growing cuts, growing uncertainty

Now more than ever, with inflation on the rise again, housing costs even for small apartments often out of the price range of struggling families, gas prices increasing and health care costs threatening to go through the roof, food insecurity is a monumental concern.

In a way, Ryan Rasmussen is grateful that so little of the assistance the Oshkosh Area Community Pantry receives comes from federal dollars.

It’s not that OACP’s Executive Director wouldn’t appreciate more federal support to help his Oshkosh community, almost a third of whose residents suffer from food insecurity. It’s just that, with all the uncertainty and all the recent federal cuts to food subsidy programs, his pantry has been better able to carry forward with their work. Non-profits who are more reliant on the federal government are scrambling to find alternatives now that the USDA under the new Trump administration cut $500 million each from both the Emergency Food Assistance Program (TEFAP) and the Local Food Purchase Assistance Cooperative Program (LFPA) last spring.

The latter of these two programs helps pay local farms to produce fresh produce for food pantries – a seeming win-win in that it provides struggling farmers with a market and at-need families with food – while one of TEFAP’s key programs buys meat, eggs, fruits, vegetables, and grains, among other items, directly from U.S. producers and offers them at no cost to struggling families.

Rasmussen’s pantry did not escape the administration’s cuts entirely, however, and is still working to help recoup those LFPA losses. One farmer in Ripon who had committed more than $100,000 in crops to be donated to the Oshkosh pantry ultimately paid the price for those sudden cuts when money promised to her through LFPA was suddenly withdrawn.

Rasmussen, who has overseen OACP for nearly four years now, says that wasn’t the only way his pantry has been impacted by actions of the new administration.

“One of the direct effects was a $10,000 grant through the Emergency Food Assistance Program that just got cancelled,” he says. “That was just straight cash. And then TEFAP cuts hit us too. There were two semitruck loads, one full of milk and one full of eggs that got canceled on us as well.”

Those hits can be significant given that this is, after all, a non-profit that isn’t in a position to absorb sudden funding shutdowns. But many other sources help sustain OACP, including Winnebago County; Community Development Block Grants through the City of Oshkosh; the Oshkosh Area Community Foundation; Fox Cares Foundation; JEK Foundation; JJ Keller Foundation; and the Otto Bremer Trust.

OACP also relies on Feeding America Eastern Wisconsin, area grocery stores willing to provide discounts or donate food that reaches a certain sell-by date, and individual donations.

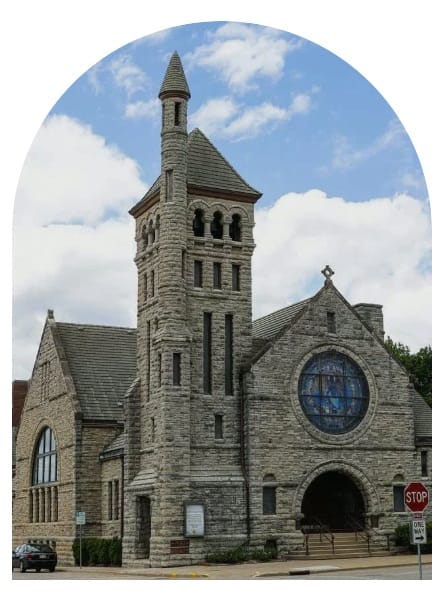

The Oshkosh Area Community Pantry occupies one-half of the Saint Vince De Paul Thrifty and Furniture Store; far right: Trinity Episcopal Church where the food pantry all began

'Our true mission'

Now more than ever, with inflation on the rise again, housing costs even for small apartments often out of the price range of struggling families, gas prices increasing and health care costs threatening to go through the roof, food insecurity is a monumental concern. Toss in cuts to Medicaid and to Affordable Care Act subsidies, the Supplemental Nutritional Assistance Program (SNAP) and so many more safety net programs and you’re looking at a potential food crisis.

The Oshkosh Area Community Pantry began as the Ecumenical Food Pantry at Trinity Episcopal in Oshkosh in 1989. First Congregational, First United Methodist, Algoma United Methodist, Wesley United Methodist, Christ Lutheran and First Presbyterian came on board to support the mission. In 2008, leaders around the area determined that food insecurity was not going to be solved either by churches or by the government and created the Oshkosh Area Community Pantry. It leases one half of a building owned by Saint Vincent de Paul Society on Jackson Street in Oshkosh.

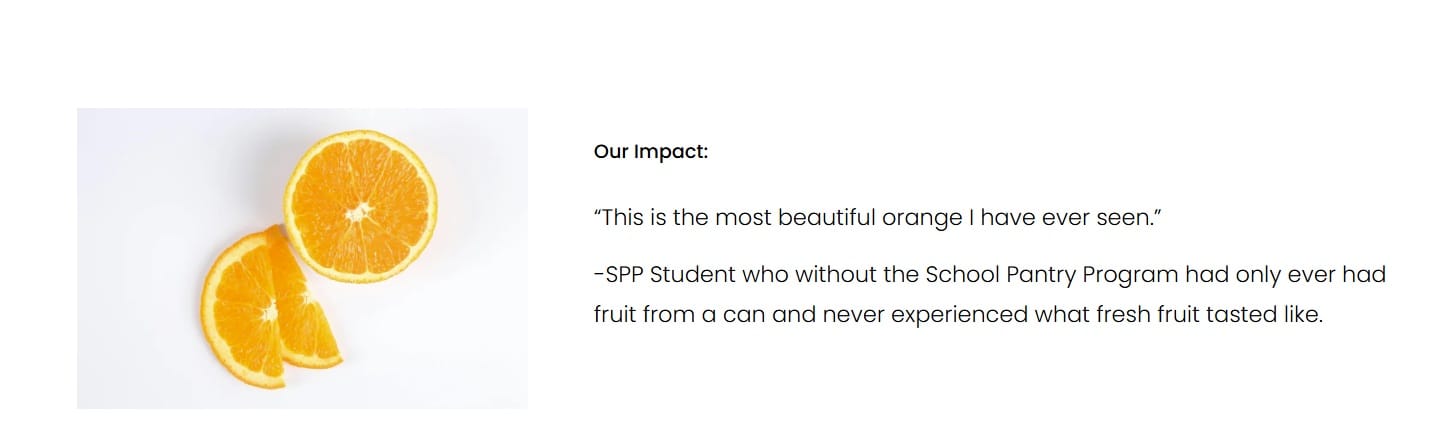

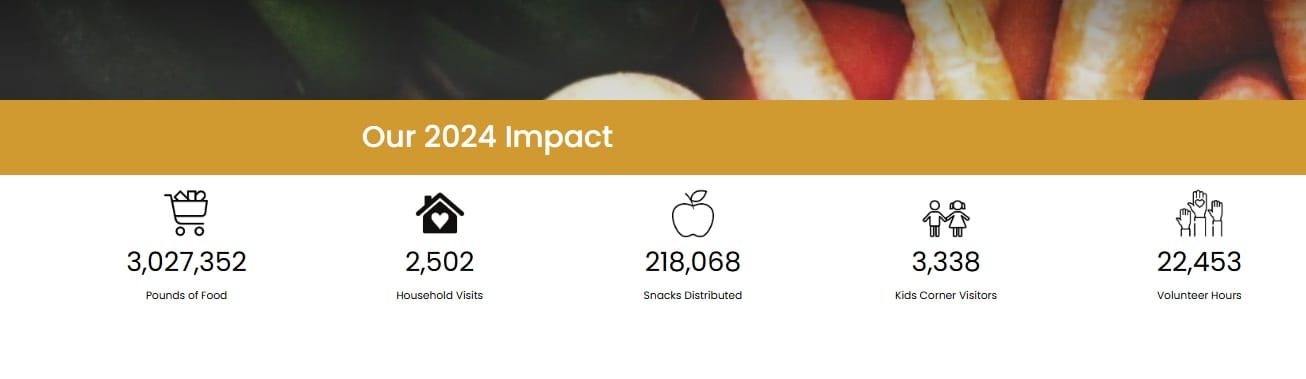

In 2024, OACP distributed over three million pounds of food; distributed 218,000 snacks through its school pantry program; and made 2,500 household visits.

The Oshkosh Pantry asks no proof of need from anyone who walks through their doors.

“Anybody can come to us and self-describe that they're facing food insecurity and we’re going to get them help,” Rasmussen says. “We recommend that they bring an ID or proof of address. It's not required. We just ask if they're willing to show it to us. Part of the reason that we ask is just for grant-writing purposes and data collection for us, our funders and the grants that we go after because they're looking for qualitative and quantitative data.”

He estimates that less than one percent of visitors to the pantry do not meet the maximum qualifying income level. But he tends not to judge those folks.

“Maybe it's not specifically food that's going for them, but maybe it's a different family member who's an uncle, who's uncomfortable being here, or maybe it's some other situation that's happening in their life. Maybe they have neighbors that they know need the extra help, but they're unwilling to do it.”

Rasmussen says he believes in the inherent good in people and is willing to give folks the benefit of the doubt.

“I mean, again, if our true mission is striving to eliminate food insecurity, well, that can happen to anybody at any point,” he says. “We truly believe we’re all one life event away from being food insecure. So we want to make sure that when folks need us, we're available. So rather than worrying about what that reason is, let's just get folks the help.”

Rising needs

Part of Rasmussen’s attitude may stem from the sheer level of need in 2025. He estimates there has been a 50 percent uptick in traffic through the pantry over the past eight months.

“When I got here four years ago we were averaging 1,300 families a month,” he says. “Today we sit at 2,800 families a month and we’re averaging close to about a hundred new registrants a month.”

Some of that was to be expected, he says. When the government rolled back its COVID-era Emergency Allotments in 2022, costing the average family $225 in monthly benefits, it hit people hard. He says the influx resulting from that has yet to plateau.

“Now we all knew that the federal government couldn't sustain that level of SNAP benefits for folks for the long term, right?” Rasmussen says. “So we all knew that at some point it would have to go back to pre-pandemic levels. The timing that they did it correlated to the time that we started seeing prices go through the roof. The housing market go through the roof. Everything else was rising drastically in price. So it just amplified the effects even more.”

According to 2023 studies, a little more than 10 percent of Winnebago County residents are facing food insecurity. He suspects that’s a lot higher, given that the qualifying income for SNAP benefits in Wisconsin – which is 130 percent of the federal poverty level of $32,000 for a family of four – begins at around $41,000. Factor in average annual rent for such a family at around $11,000 and add in the costs of transportation, medical care and other living expenses and money for food can become scarce. Then, too, childcare costs can squeeze a family beyond the breaking point.

Because of that, Rasmussen figures the number of people facing food insecurity in Winnebago stands at closer to one-third, or about 20,000 people.

Rasmussen and Inventory Manager Larson Cook are two of only a handful of people who are paid employees of OACP, with nearly 99 percent of its workers serving as volunteers. Rasmussen says that if you count every unique individual who gave even an hour of their time, the pantry had 230 volunteers over the past year. Those volunteers logged nearly 22,500 hours last year. Ninety percent of OACP’s contributions directly reach people in need.

Pay to farmers eliminated by cuts

When the administration gutted the both the Emergency Food Assistance Program (TEFAP) and the Local Food Purchase Assistance Cooperative Program (LFPA), Tracy Olden, owner of Olden Organics Farm in Ripon, was sitting on $124,000 worth of crops, all planted under the promise of government purchase and all destined for food pantries around the area, including Oshkosh. Olden was facing a total loss.

Yet Olden never had any hesitation about contributing the food, even if the government refused to pay her.

“Honestly, I give a lot of credit to Tracy, because she instantly said, ‘no matter what, that food's coming your way.’” Rasmussen says. “My main directive then was, how do we get the story out there? How do we talk about this, and then how do we start fundraising so that way we can help reimburse some of that produce that she was already committing to us. Because she's an amazing farmer, and she has food, and she's always said, she may not be rich in money but she's rich in food. And so she always wanted to give back in that way.”

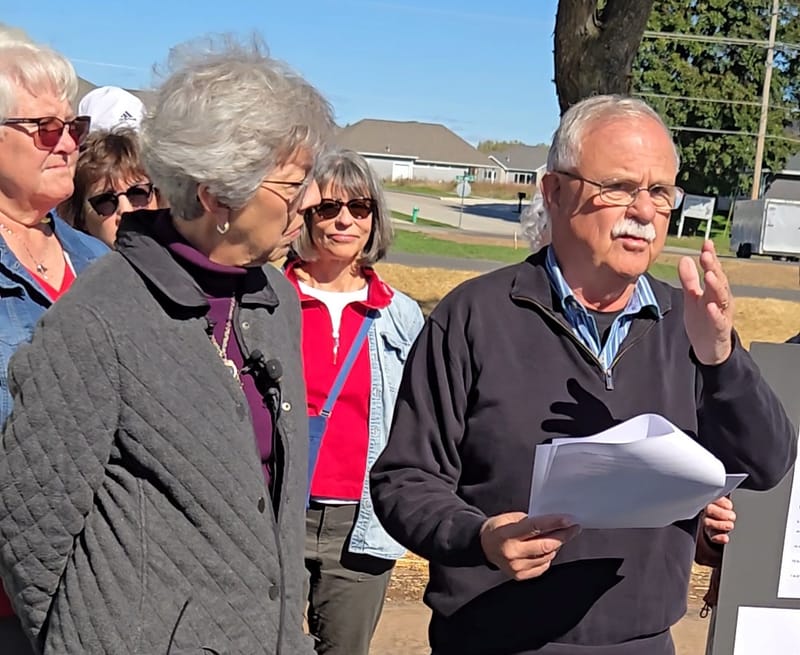

Working with other partners in the community, including the Oshkosh Area Community Foundation, Winnebago County and the Women Who Care of Greater Oshkosh and getting the word out about the government’s reversal of the LFPA program and the community’s needs, OACP has been able to recoup nearly half of Olden’s costs.

“After we found out, Ryan and I started brainstorming and pounding the pavement, talking to people, trying to get people to help feed their local community,” Olden says. “And people stepped up. Oshkosh has a huge need and it’s really turned into a great partnership with Ryan.”

"We can offer them 45 minutes while they're shopping here to just take what you need. Relax. You don't have to worry about those things that are happening outside for those 45 minutes while you're here." – Oshkosh Area Community Pantry Executive Director Ryan Rasmussen

Such uncertainty is the norm these days, say Rasmussen and Cook, who must navigate the recent government cuts as well as food availability, which has become a question mark given President Trump’s wavering tariff policies.

“I think the challenges that we see on our end right now is there's no clear direction and there are no answers,” Rasmussen says. “Anytime that we are in meetings with state representatives or DHS, or any of the folks that we would typically turn to and say, ‘Okay, what's next or what's the next order, or how much, or how little are we getting?' … before, we could get a pretty decent answer.

"There's nothing right now. I mean, everybody is still just trying to sort out the what-ifs, and I think that's the most frustrating piece, is that nobody has any clear direction of what's next because they don't know yet. And because they don't know that then puts us in a position of, okay, how do we order? How do we budget, how do we make sure that the guests that rely on us get what they need.”

Rasmussen uses the example of peanut butter. If the state last minute tells him he’s got a discounted buy on peanut butter but OACP has just purchased $20,000 worth of peanut butter because he was out, that’s money out the window that he could have used elsewhere.

“Pantries, inherently, are always the last stop in the food train before waste,” Rasmussen explains. “We usually have to look to retailers to kind of gauge some of the things that we're going to start seeing. We can usually kind of dictate some of the items that are going to be coming downstream to us. And even right now, we don't know. We have none of that. We have none of that predictability.”

Real people, real needs

The work, despite the frustrations, remains satisfying to both Rasmussen and Cook. Cook, who had been on the food banking side of the equation for 16 years before coming to OACP three years ago, says he enjoys seeing the end result of it all – people walking out the door with the food they and their families need.

“It’s satisfying to me because I see the goodness of people,” Cook says. The guests that come in, the volunteers, the donors. Yeah, I think we all want the same thing.”

Rasmussen and Cook witness real people benefit in ways that keep them off the cliff’s edge of severe hunger. Judy is 81 and says her rent, prescription and doctor bills are all getting higher and higher.

Jess is a single mom who isn’t quite certain how she and her child could survive without the OACP.

“It’s so hard sometimes to not know where your next meal will come,” she says. “With the help of the pantry, I’m able to make it happen.”

Branden says he and his boyfriend recently moved to Oshkosh and didn’t have food to eat most days before they discovered the pantry.

Megan says it is a relief to no longer worry if she’ll have enough to feed her family.

“This has been a saving grace during this time of inflation and uncertainty,” she says.

For Rasmussen, an Oshkosh native who spent years in the food service industry, being able to help his community is the real blessing.

“This has always been home, and so for me, being able to still be at home in the community that I love, in the food industry that I love, and being able to give back to the people that are in this community has just been so rewarding,” he says. “Because these truly are the neighbors that I grew up with and and I'm able to see through good, bad struggles, all the things that they're dealing with in life.

“They can come here and have just a sense of normalcy for just a brief moment before they have to go back outside and deal with whatever they're dealing with. And that, to me, is the best, because we can offer them 45 minutes while they're shopping here to just take what you need. Relax. You don't have to worry about those things that are happening outside for those 45 minutes while you're here, and that's what's impactful for me.”

Oshkosh food pantry meeting needs despite growing cuts, growing uncertainty © 2025 by Kelly Fenton is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0