As it nears 50th anniversary, Individuals with Disabilities Education Act faces threats

On November 18, Secretary of Education Linda McMahon began dismantling the Department of Education, the department responsible for overseeing and enforcing the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act. Funding for students with disabilities has not yet been reassigned to another department

The 50th anniversary of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) is coming up at the end of this month. IDEA was signed into law on November 29, 1975, finally granting the right to a free and appropriate education for students with disabilities.

IDEA required schools to identify and evaluate students thought to have disabilities and provide them with appropriate support. Congress intended to fund up to 40% of the additional per-student cost, but it has fallen way short at just 13%.

Members of Congress have recently introduced the IDEA Full Funding Act (H.R. 2598), which would create a ten-year mandatory path for federal funding until the budget line reaches the 40% promise.

Still, critics of recent federal and state policy warn that those protections, a half-century later, are being watered down.

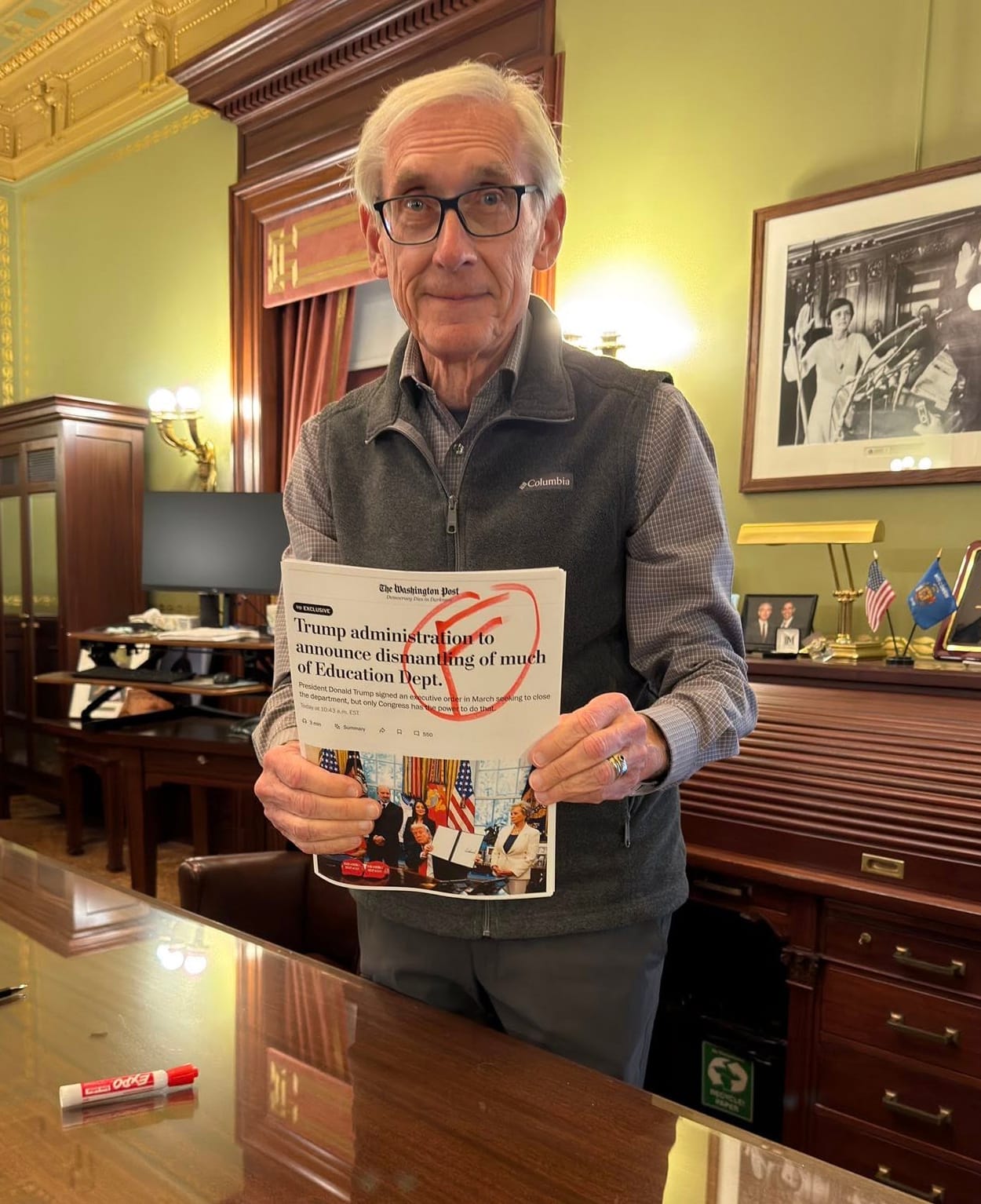

On November 18, Secretary of Education Linda McMahon began dismantling the Department of Education, the department responsible for overseeing and enforcing the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act. Funding for students with disabilities has not yet been reassigned to another department, though it is expected that McMahon will seek to transfer IDEA to the Department of Health and Human Services by the end of the year.

Scattering programs across multiple agencies that are not equipped to provide the same support and services will weaken federal oversight, gut funding, and dismantle protections for students with disabilities, warn critics.

Gov. Tony Evers gave McMahon’s plan a grade of ‘F’.

“The Trump administration seems to be targeting the most vulnerable students in their defunding and dismantling of the federal Education Department,” said Dr. Julie Underwood, Dean Emerita of UW Madison School of Education and an expert in education law, policy and funding. “It doesn’t make sense and it is just plain cruel.”

Patty Clark-Stojke is a former speech pathologist and says it is essential the government continues to provide oversight for programs like IDEA.

“The rules and regulations I followed came down from the federal government,” she said. “That is the entity that monitors important things like the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA). And I just fear that when we lose those protections, what happens to the children? And what happens to the funding that provides that service? What happens when an educator or a parent feels a child needs more but it’s not available? What are the kids going to lose?”

Wisconsin funding for special education still lags

It is not only the federal transfer of IDEA oversight to an undetermined department that is threatening the rights of students with special needs in Wisconsin, it is also the low reimbursement rates for special education in the state. In the 1970s, that rate reached 70%. A few years ago, it was as low as 29%.

In the recent state budget negotiations, school districts across the state advocated a bump to 60% but ultimately had to settle for 42%. It was recently reported to be at only 35%. That means special education funding is already approximately $140 million short of what was promised, leaving school districts across the state scrambling to pay for underfunded mandates.

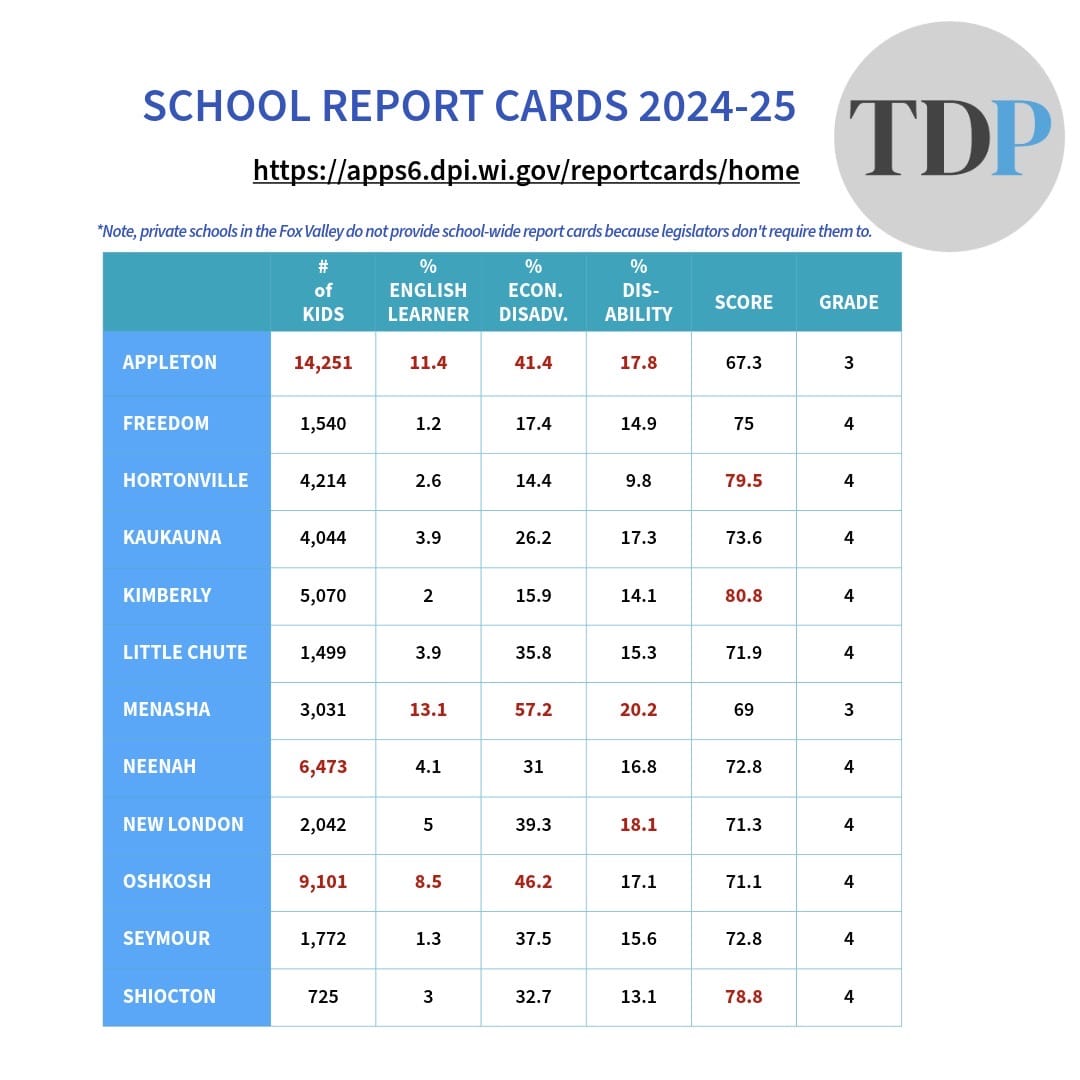

The demographic information in the graphic above shows the current percentages of students in local school districts that require additional resources and, therefore, increased funding.

There appears to be a clear correlation between the percentage of high-needs students (which includes, in addition to students with special needs, the economically disadvantaged and English Learners) and the report card scores. A rating of ‘three’ means meets expectations. A ‘four’ means exceeds expectations.

The only two out of the 12 districts receiving threes had the highest and third-highest percentage of students with disabilities.

As far back as 1999, a bipartisan Blue Ribbon Commission recommended increased funding for these priority-needs students. The legislature has yet to act on any of its recommendations.

In 2000, the Wisconsin Supreme Court, in Vincent v. Voight, ruled that the state was not adequately funding public schools in three areas: Students with Disabilities (Special Education), English Language Learners (ELL), and children from low-income homes (Free and Reduced-Price Lunch).

Furthermore, there is a discrepancy when it comes to special education funding for state and private schools.

The state funding of public-school students with special needs is ‘sum certain’ which means a specific set amount is allotted for special education. When used up, that is it, no matter the number of students being served or the costs of the support. Most high-needs, high-cost students remain in public schools.

In contrast, the special education voucher for private schools is ‘sum sufficient’, which means the funding to cover all its costs is guaranteed.

On average, school districts across the state transfer 10% of their general education budgets to fill the gap created by mandated and required services for students with special needs. As a result, educational opportunities for all students are impacted by the underfunding of special education.