AASD discusses tough choices ahead for education at forum

School districts across the state have been hamstrung for decades by revenue limits imposed by the state legislature, which began in 1993.

At a public presentation on Oct. 3, Superintendent Greg Hartjes acknowledged that there are no good options for the financial bind the Appleton Area School District finds itself in, which includes a $13 million deficit.

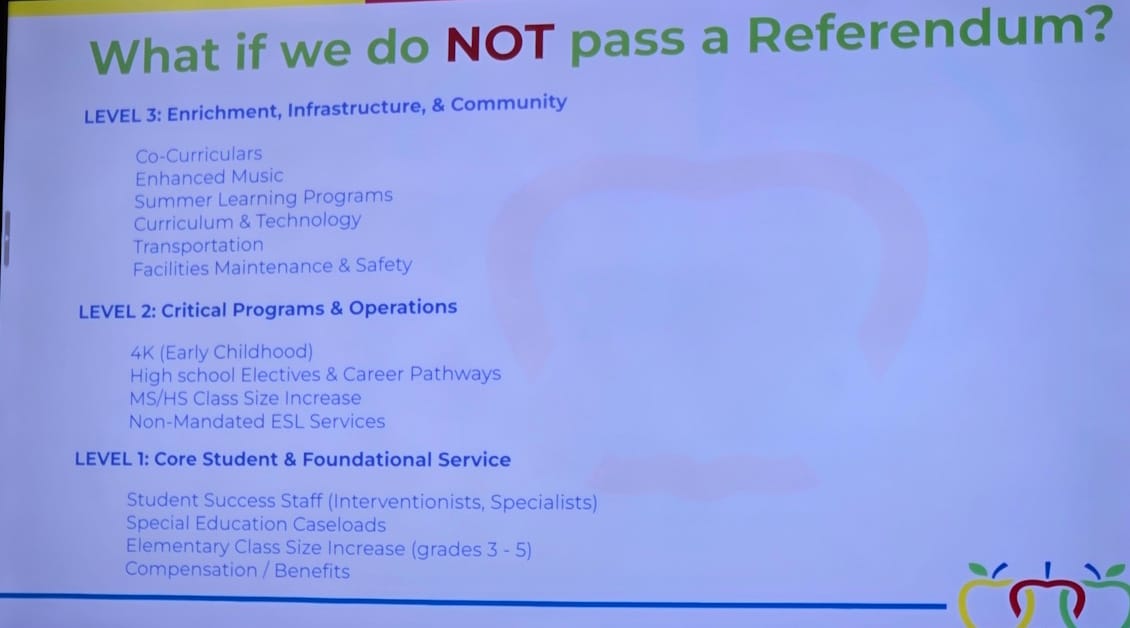

Any proposal put forward in 2026 would be an ‘operational’ referendum covering normal operating expenses, such as salaries, maintenance, utilities, and other inflationary costs. Without additional funding, the district would be forced to consider cutting staff, eliminating programs, or even closing schools.

The district is just three years removed from a successful ‘capital’ referendum that passed with 67% of the vote. It resulted in a new school, as well as numerous upgrades to existing buildings.

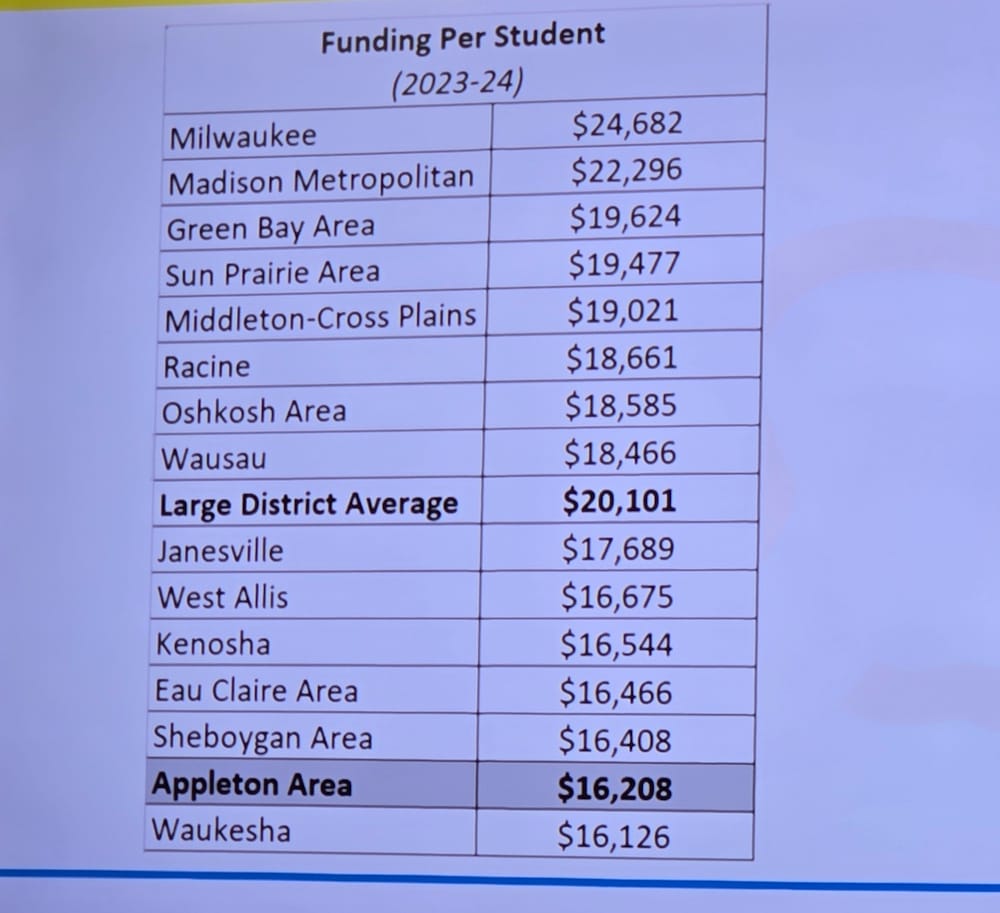

Out of 15 comparable-sized school districts, Appleton ranks 14th in spending per student. Should the district need to cut $13 million from its budget, it would rank dead last.

“So if we don't vote a referendum or we don't pass a referendum, we have to cut $13 million from our budget,” said Hartjes. “We drop below every large district in the state by a considerable amount.”

School districts across the state have been hamstrung for decades by revenue limits imposed by the state legislature, which began in 1993. Revenue limits refer to the amount a school district can collect from state general aid and local property taxes. School districts, like Appleton, that operated frugally in 1993, have been at a disadvantage ever since. Revenue limits can only be increased through legislative action.

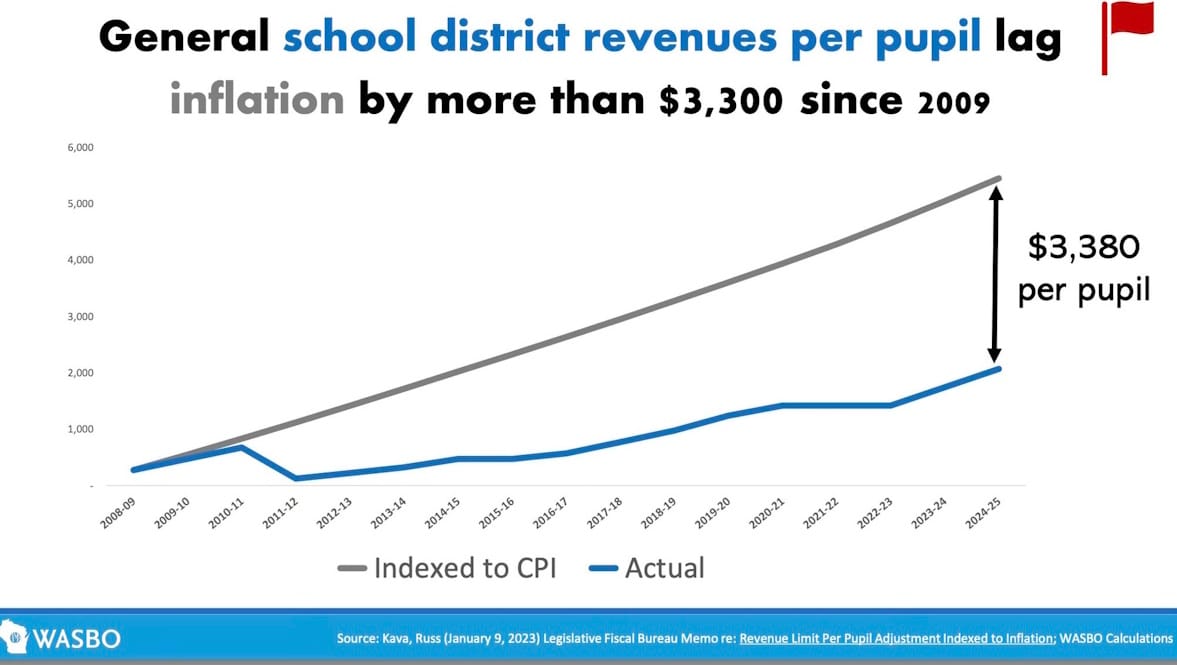

Public education has faced additional headwinds beyond the revenue limits. When those were imposed in 1993, a yearly inflationary increase was automatically built in. That changed in 2009, when yearly Consumer Price Index (CPI) increases were eliminated. From that point on, legislative action was required for any inflationary increases, which has only occurred three times since. Therefore, school districts have fallen further and further behind every year, forcing yearly cuts and tough decisions. Referendums have been their only solution.

“Over this last stretch of years, we've not kept up with inflation so much so that the difference now if we had kept up with inflation (would have been) $3,380 more per student,” Hartjes said. “We would have 50 million more dollars every year to spend on educating our students if we were still tied to the CPI (consumer price index). So that's the first challenge that every district in the state is facing.”

To make matters more difficult for public schools, the current state budget added no increase in state general aid for public education. Even though two years ago, Gov. Evers offered a $325 per-student increase, with no additional state funding, taxpayers themselves will be forced to cover the cost.

“What I'm paying for my kids, and what this community is investing in our kids is $4,000 less per student than was invested in me in those dollars, and that's the challenge,” said school board member Oliver Zornow. “And so I am glad we are looking at addressing that fact because I think that's morally wrong.”

Other issues plaguing AASD and districts around the state include the lack of transparency regarding private school voucher costs, the rising costs of health insurance, and the ongoing underfunding of special education. All these add stress to public schools and taxpayers. Based on inflation-adjusted numbers, current Appleton school taxes are actually 40% lower than they were 14 years ago.

The cost of private school vouchers to AASD property taxpayers is now over $8 million annually. In addition, private schools generally do not serve high-needs, high-cost students, leaving the public schools to absorb the added expense.

While AASD has tried to stay ahead of health insurance increases by changing providers, increasing employee contributions, and developing partnerships with clinics, pharmacies and other school districts, the cost to the district rose by more than $10 million from 2020 to 2024 and is expected to go up another $3 million this year.

Public schools did receive an increase in their reimbursement rates for special education in this current budget, but only up to 42%. Voucher schools receive a 90% reimbursement rate. At one time, public schools enjoyed a 70% reimbursement rate.

Eighteen out of every 100 AASD students need special education services, and that money further reduces the general fund at AASD. That amounts to about $27 million each year.

The crunch public schools face is evident in the sheer number of referendums placed before voters. In the last two years, nearly half of the 421 school districts have asked voters to pass an operational referendum. The majority have passed, suggesting voters are willing to pay for public schools.

Zornow encouraged all the community attendees to continue sharing their thoughts. “These are big decisions that will impact the next 100 years of development in our community,” he said. “We need to make the right decisions, and we need all the ideas on the table. Public comment (at school board meetings) is a great opportunity to share. If you don't want to speak publicly, you can always send us an email or catch one of us individually.”

A second listening session will be held at 6:30 p.m. on Oct. 7, also at the AASD Welcome Center. A community survey and other community informational sessions are being planned. After gathering information from the community, the school board will decide by January whether or not to present a referendum question to voters.

AASD discusses tough choices ahead for education at forum © 2025 by Carol Lenz is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0