With funding gone, child care owners warn of dire future

A survey estimated 1,000 centers around the state will close -- nearly one in four --and 30,000 more openings will go unfilled. Forty percent anticipate raising tuition 35 percent; 75 percent will have longer waiting lists and 40 percent will have to close some classrooms.

Mention infrastructure and what likely pops into your head is a road or a bridge or maybe a utility or broadband cable.

If someone offered child care as an example of infrastructure, though, you might find yourself scratching your head.

But inasmuch as infrastructure refers, generally, to the foundation and structure on which more visible systems operate, it’s hard to argue that child care doesn’t fall into the category. If, more narrowly, you define infrastructure as one of the underpinnings of our social and economic cohesion, you have an even stronger case to make for child care.

It’s a debate that has been ongoing for decades but in June 2025 it has taken on an urgency which everyone says they feel even if, policy-wise, that isn’t being reflected.

On July 11, Wisconsin, short of a last-minute amendment to the state budget, will cease funding for Child Care Counts, bringing to an end four years of Covid-relief subsidies which all available data suggests has helped hundreds of child care centers survive. That leaves it up to the state to provide ongoing support. Wisconsin has been operating over the past two years on Gov. Evers’ $170 million in emergency funding, which also came from ARPA money.

Democrats in May offered $480 million to shore up the industry and Gov. Tony Evers included it in his budget proposal. But GOP lawmakers removed it and now people who work within the industry – many of them owners of child care facilities themselves – are warning of dire consequences.

“As funding for the state’s child care facilities dwindles and accessibility for families shrinks, it is absolutely essential that we invest in our children, families, communities, and economy,” says Rep. Lee Snodgrass, a Democrat from Appleton. “Child care impacts everyone.”

Crisis Mode

Missy Hughes, Secretary and CEO of Wisconsin Economic Development Corporation (WEDC), warns of ripple effects, especially given that the state is currently in a workplace crunch with a shortage of workers.

“(Without affordable access to child care), parents are staying home; they’re not contributing to the economy; their income is probably less; and then businesses don’t have access to that workforce,” she says.

Child care didn’t just now reach this crisis point. It’s been a looming issue for years, not just in Wisconsin but across the country. With more two-family incomes necessary to make ends meet, child care poses a more urgent need than ever and the influx of federal relief dollars following Covid was always just a temporary fix.

“Those Covid relief dollars put us in a really great position to be able to help pay our teachers more,” says Julie Stoffel, owner of Cradle To Crayons Learning Center in Kimberly. “I mean, staffing has always been an issue. So I always say to people, long before Covid happened and we received this stabilization fund, child care was already in crisis mode.

“We run on razor-thin margins and we’re trying to make the budget balance which is always difficult. We only have so many spots we can fill. So when that money came through we were able to bump up some wages and to freeze rates for some of the families. But mostly it was about being able to keep staff. Most businesses are generating huge revenue but for us it’s just break even. I always say we are a for-profit industry but we are usually running like a non-profit.”

You can clearly see the crisis in the numbers. Wisconsin is considered a child care desert, defined as one available child care slot for every three children. In some rural areas that number is one for every five.

There are 4,400 child care centers of one form or another in the state. More than 6,000 have closed over the past decade. Sixty-four have closed in Outagamie County in that span with only 98 remaining. Those numbers mean little unless you understand what it means for parents. Across the state there are 117,000 slots unfilled due to the shortage of centers and teachers. Outagamie County currently has a shortage of 5,900, meaning parents of nearly 6,000 children are on a waiting list for an opening, if they can even afford it.

It is estimated by the bipartisan child caregap.org that the Wisconsin economy loses as much $6 billion a year due to this inability to fill child care slots. Outagamie County loses $188 million.

And though those who oppose extending Child Care Counts offer up muted suggestions for the industry – deregulation, more students per teacher, raising costs, tax credits, etc. – the truth is, none of those are fixes for a variety of reasons and would likely make the situation more dire.

(Cradle To Crayons Learning Center Facebook Page)

Ripple Effects

The cost per year for two children in a typical child care center is nearly $29,000. Thus, raising prices is unsustainable and in an industry that gets by on a mere one percent margin, lowering them is impossible. Wages are so low for teachers – at an average wage of $13.66 an hour, child care teachers rank 543rd out of 556 occupations – that they need to grow, not shrink. And it is grueling demanding work. Thus, retention is another constant headache for owners.

As for some Republican lawmakers’ suggestion of allowing more children per teacher, that would be sure to drive even more from the industry when shortages already abound. Not to mention the inhuman demands on underpaid workers and the impact that their diluted attention would have on the children themselves, for whom that daily interaction is critical to brain development.

This is how the child care industry becomes infrastructure. Without it, whole systems have to adapt. The economy suffers; families suffer; children suffer.

“It impacts your household because you’re trying to survive on one income,” says Corrine Hendrickson, owner of Corrine’s Little Explorers Family Child Care near Madison and the co-founder of WECAN, a non-profit, all-volunteer advocacy group for the industry.

“More people qualify for Medicaid; more people qualify for food stamps. If somebody gets pulled from the workforce, that decreases their trajectory and their retirement savings.

“And then if your household is down to one income, you're not paying nearly as much in taxes (which means less government revenue). And there are people willing and able to work, and there are employers looking for employees, and the missing piece is that availability of child care”

Hendrickson goes further, noting the impact all of this has on local economies when families make less money and now can’t go to that local restaurant as often and sales tax revenues dwindle and businesses aren’t as profitable.

The frustration for many parents and people who work within the industry is that child care was among the top issues articulated at the Joint Finance Committee listening sessions over the past several months. Republicans have ignored those pleas and have instead offered an expansion of the federal child care tax credit for families struggling to afford child care. While the credit could theoretically provide a subsidy of $4,000 per child per year, there is a critical catch. A family could not receive a credit greater than their tax liability, meaning those lower-income families who otherwise might qualify for a large credit could only receive an amount up to their tax liability. Child care industry experts told the GOP that the plan was woefully inadequate and furthermore failed to address the critical teacher shortage.

“We’ve done everything we were told to do,” Hendrickson told the Wisconsin Examiner in May. “We showed up. We shared our stories. And still lawmakers voted to cut child care from the budget. No plan. No replacement. No respect.”

While the GOP continues to refuse to fund child care, area Democratic legislators are pushing hard.

“Child care is the infrastructure of our economy; it’s the industry upon which all other industries rely,” says Sen. Kris Dassler-Alfheim. “Renewing the Child Care Stabilization fund will pay for itself in the long run and it’s an essential piece of the puzzle when it comes to addressing the current child care crisis. Allowing it to expire will have catastrophic consequences, not just for the providers and the children and families they serve, but for every single industry in Wisconsin.”

Relationships, relationships, relationships

It is estimated that the return on every dollar of child care investment is tenfold. Despite that, Wisconsin remains one of only six states that does not invest in its child care. Hendrickson points out that that $480 million proposed by Democratic lawmakers represents just a small fraction of the state's nearly $5 billion surplus, but would make a huge difference.

“Just 10 percent of that surplus would completely stabilize our industry and provide early education teachers with a $10 an hour rate increase (to $23),” she says. “We understand money doesn't grow on trees, but we're not asking for a handout. We're asking for investment in Wisconsin's future.”

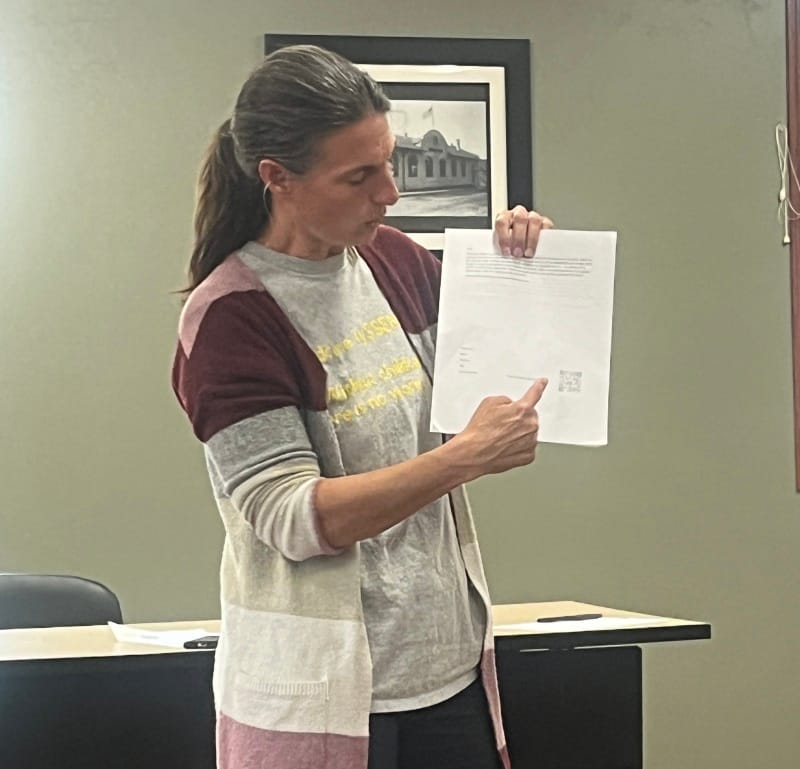

This isn’t just about money or the economy, Hendrickson stressed at a public forum on the subject in Hortonville recently. It’s about the impact on the children and their futures. She pointed out the differences between the development of a brain under stress and one that is functioning under mostly healthy, stable circumstances. A child’s brain, especially, is susceptible to external forces such as a lack of stability, constant disruption, interruptions in their vital relationships, etc. These are known as ACEs or adverse childhood experiences. She points out that the child care teacher can be the most consistent presence in that child’s life in those developmental years.

“It’s relationships, relationships, relationships,” she emphasized. “And a typical middle class child is not going to have a lot of ACEs. But we as a society expect that the child who has had neglect is going to have the same exact outcome and the same opportunities as the (non-stressed) child. That’s absolutely not true unless the child gets significant intervention.

“And then we get surprised when they end up being expelled and wonder, ‘what is wrong with this child?’ instead of ‘what happened to this child?’”

Then, too, there are the physiological impacts on children that lead to the three big afflictions in later life: cardiovascular disease, diabetes and depression. Hendrickson says that the dramatic turnover in teachers makes it difficult for that vital and consistent one-on-one a developing child needs.

What lies ahead?

So with so much at stake, what might we expect to see happen to the industry if its subsidies are pulled away. A survey of child care center owners around the state paints a bleak picture, perhaps even more so than before the stabilization funds were dispensed four years ago.

During those four years, for the first time in more than a decade, more centers opened than closed. The survey estimated 1,000 centers around the state will close – nearly one in four – and 30,000 more openings will go unfilled. Forty percent anticipate raising tuition 35 percent; 75 percent will have longer waiting lists and 40 percent will have to close some classrooms.

Solutions are available, even beyond the ones that WECAN (Wisconsin Early Childhood Action Needed) and other advocates have pressed upon Republican legislators. Vermont has imposed a .44 percent payroll tax, which has doubled state revenue for child care. Since last April, Vermont has increased slots by a thousand, opened 40 new Family Care Centers and 100 new youth centers.

“Here, (a .44 payroll tax) gets us $1.6 billion,” Hendrickson says. “It would allow us to raise teacher pay to $23 an hour.”

Connecticut went a step further, imposing a 1.5 percent natural gas tax and the industry is now fully funded in the state. Hendrickson says more and more businesses are getting behind the push for child care support. They recognize, she says, just how much this impacts them as well.

Both Stoffel and Hendrickson agree that the most impactful investment needs to be in teacher pay. The research shows that states that invest in teachers had the best results and lost the fewest number of programs. Fewer and fewer people are choosing child care in college and it’s not hard to see why, given that the field continues to pay near-poverty wages.

“Even those of us in the field are not telling people to get in, because you shouldn't,” Hendrickson says. “I mean, in good faith you should not. It's important because what we do is so valuable, and that's why they're fighting to get the funding. But at the same time, this is what we're looking at. This is the reality.

“But our system has always relied on women – mostly women – being willing to work for less than they're worth in order to subsidize the system on our own back. We've always done that. That's how our system has been created.”

As for people like Julie Stoffel of Cradle To Crayons, she remains passionate about what she does and is willing to hang in as long as she can.

“I spend many nights crying about the fees these parents are paying and about having to write the letters and say, we’re gonna have to go up another twenty dollars a week,” she says. “Any other industry would not even bat an eye but when you’re talking about families and livelihoods and about women who have to choose between giving up a career and staying home. No one should be judged on that. And Wisconsin used to lead with women in the workforce. And we’re not there anymore.

“People ask me all the time, ‘How long are you going to do this?’ And I say as long as we can. I say that day I finally see our early care and education system in Wisconsin supported like it should be, then I’ll step away. It’s sad what these young children and young families are grappling with.”

With funding gone, child care owners warn of dire future © 2025 by Kelly Fenton is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0