Asthma legislation aims to reign in PBMs, cap patient copays

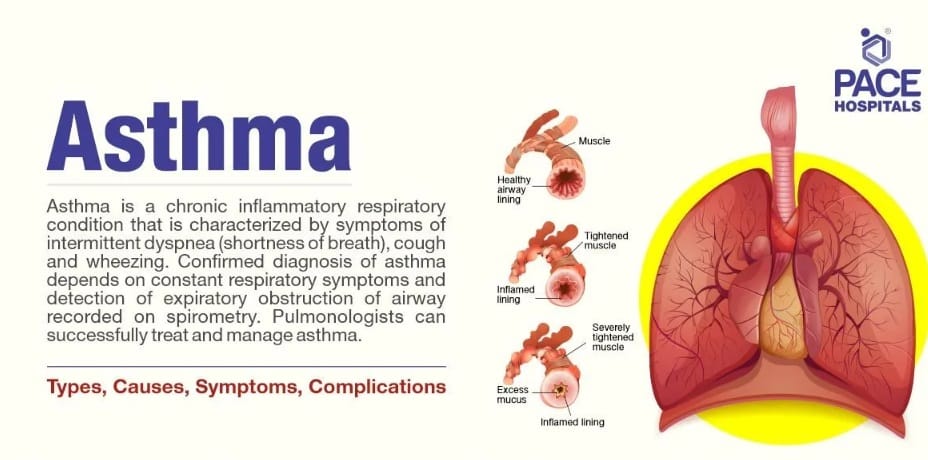

Nearly eight percent of Americans suffer from asthma, a chronic, often debilitating disease that causes inflammation of the airways. Lower-income, Hispanic, Black, Native-American and the elderly make up a significant percentage of the more than 25 million Americans afflicted by it.

Ellis’s parents called it dragon breath, just to try to make a game of it.

Dragon breath was the vapor that used to escape from the nebulizer six-year-old Ellis used when he was younger to help tamp down his asthma.

Though Ellis has grown old enough to graduate to a twice-a-day inhaler and leave the nebulizer behind, it’s still daunting for a kindergartener to have to put a tube in his mouth and relax enough to breath in the spray that keeps his lungs functioning properly. So when it’s time for him to go through the ritual each morning and evening, mom Christina asks Ellis to “go get your dragon’s breath.”

“He was like a little dragon shooting smoke out of his nose,” she says. “And that felt, I don’t know, cool instead of annoying or scary.”

Ellis is one of Christina and Brian Leone-Tracy’s two adopted sons. While Ellis’s nine-year-old brother, Nevan, is not troubled by asthma, Christina suffers from it as well. Though no specific gene for asthma has been identified it is considered a genetic disorder. Ellis’s biological father has it, too

Ellis is an energetic, curly-haired kid who wears cool blue-framed glasses with bright green earpieces. He loves soccer and gymnastics. His inhalers allow him to remain active and lead a mostly healthy six-year-old’s life.

Christina has a much less severe case of asthma than her son. Hers is almost always induced by virus or exercise and manifests as tightness in her lungs. Ellis’s is serious enough to have landed him on more than one occasion in the emergency room.

He wasn’t officially diagnosed until two months ago, but only because it is so difficult to run the necessary tests for kids that young. After Ellis’s last trip to the ER back in November, his parents went to see a pulmonologist at Children’s Hospital in Milwaukee. The first available appointment with a pediatric pulmonologist in Appleton was May.

As is typical with so much health care in America, Leone-Tracy ran into insurance issues when she tried to fill the inhaler the ER prescribed. With a history of medical issues herself, she knows too well the hurdles patients must clear to get coverage approved.

“Whatever it was the doctor prescribed it took us three weeks to get the correct inhaler approved by insurance,” she says. “At first they didn’t want to give us any of them and then they didn’t want to give us the one that he really needed. I’m used to fighting with them but I’m like, really? You’d rather him be in the ER than just paying for the inhaler. That seems more expensive.”

Ellis now has his daily inhaler and two rescue inhalers – one at home and one at school – for when he is struck by a life-threatening case.

Two new pieces of legislation in the Wisconsin state legislature have been drafted to deal with asthma, from costs to mandated coverage to reigning in the pharmacy benefits managers that determine all aspects of a patient’s coverage. The fate of both bills remains uncertain.

Record profits come at patients’ expense

Nearly eight percent of Americans suffer from asthma, a chronic, often debilitating disease that causes inflammation of the airways. Lower-income, Hispanic, Black, Native-American and the elderly make up a significant percentage of the more than 25 million Americans afflicted by it. In 2023, more than 3,000 Americans died from asthma complications.

Needless to say, asthma sufferers who contracted Covid can face even more serious complications.

While most insurance covers asthma medication, not all do and the cost can be prohibitive, upwards of $3,000 a year. In one tragic case from 2024 Wisconsinite Cole Schmidtknecht died when his pharmacy benefits manager (PBM) removed his life-supporting inhaler from his drug formulary, and his cost went from $66 to $540.

PBMs are the middlemen who decide which drugs an insurance company will cover and to what extent. Though they were created with good intent, today only three PBMs cover 89 percent of the market and this leverage resulted in profits of $330 billion last year, leaving patients often frustrated and bereft of life-saving coverage.

Cole’s father, Bil, has been on a crusade to hold PBMs accountable for actions that leave people’s lives on the line in the interest of greater profit. His website provides key information about PBMs' outsized role in insurance.

“I witness patients facing exorbitant copays for medications they cannot afford and they’re forced into impossible decisions about their health,” pharmacist Larry Crowley told the Daily Dodge in a recent article. “At the same time, independent community pharmacies are being reimbursed at unsustainable rates far below the PBM owned pharmacies that dominate the market.”

Wisconsin State Senate President Mary Felzkowski and Todd Novak introduced the Cole Act in March to reform PBMs and increase transparency.

Earlier this month, Rep. Lee Snodgrass and Senator Kris Alfheim-Dassler introduced a bill to mandate that insurance plans that provide coverage of prescription drugs cover “drugs and related medical supplies for the treatment of asthma.” The bill stipulates that that includes asthma inhalers as well as items necessary to effectively and appropriately administer a prescription drug prescribed to treat asthma.

Capping Cost-Sharing Costs

It further caps out-of-pocket copays to no more than $25 for each one-month supply for each drug prescribed to treat asthma and no more than $50 total “for all related medical supplies.”

“As costs of living continue to rise, we are seeing a growing number of people forced to choose between essential medication and basic necessities,” Snodgrass said in a press release. “Nobody should go to a pharmacy to pick up life-saving medication and be forced to walk away empty-handed because the cost of their asthma inhaler went through the roof without notice. This bill addresses a critical step towards ensuring asthma patients can afford the medicine they need without undue financial burden.”

Dassler-Alfheim noted that more than a half-million Wisconsinites live with asthma or other respiratory illness.

“This legislation isn’t just going to save lives – it’s going to have an immediate impact on people’s bottom lines and on the overall health of our communities,” she said. “Wisconsinites should not have to choose between paying their rent and purchasing life-saving medication. With this legislation, which has already been passed in four other states across the nation, they won’t have to.”

Michelle Morris is another local woman who suffers from asthma and was happy to see new legislation regarding insurance. Her mom also suffers from it and, while it’s hard sometimes to determine how much exactly insurance companies are charging in copays, Morris says she thinks it’s around $60 for a 90-day supply.

She says her mom’s has gotten worse since she got Covid and she must now use an inhaler twice a day. Morris herself requires only one dosage a day. Like all asthma sufferers, they also have a rescue inhaler for severe attacks.

‘That’s how they end up dying’

“So the savings for me might not be that great but it is for people who are, you know, struggling otherwise financially,” Morris says. “Over the course of a year, that could make a difference. So, yeah, I really think about other people, and then there's people that don't have any insurance, and then they're so unaffordable.”

Because pharmacy costs are so fluent and hard to decipher it’s always difficult to ascertain the exact price of any medication but Arnuity, the brand of inhaler Morris uses, averages $195 for a 30-day supply. For a twice-a-day user that cost doubles.

For Leone-Tracy, who suffers from various medical ailments, much of the frustration she feels is over just such ambiguity and with dealing with PBM representatives who make it so difficult to get an approval and who often don't know anything about the medications they are rejecting, some of which the doctors themselves are still trying to understand. She says she and her family spend around $20,000 a year out-of-pocket for their medical needs.

To get that right inhaler for Ellis last November for example – and to get it covered – they had to go through reams of paperwork and try to hunt down the ER doctor on call to provide authorization. Leone-Tracy, a minister at the Unitarian Universalist Church in Appleton, has no doubt that the hoops insurance makes people jump through are strategic.

“The thing I often say is that it’s a part time job to manage not just the appointments but the advocacy to fight the denials and the snafus and the prior authorization requests,” she says. “It’s so much energy and, you know, I have every privilege. I speak fluent English. I’m educated. I have a flexible job. I have insurance. I have enough money to pay for these things. And it’s still a nightmare.

“And I just think, you know, I don’t know how anyone who has even one less privilege than I do manages. And the truth is, they don’t. That’s how they end up dying.”