Long-term care gets state money but Medicaid cuts loom

The cost for a residence in a long-term care facility runs from $9,000 to $11,000 per month. Medicaid covers two of every three residents.

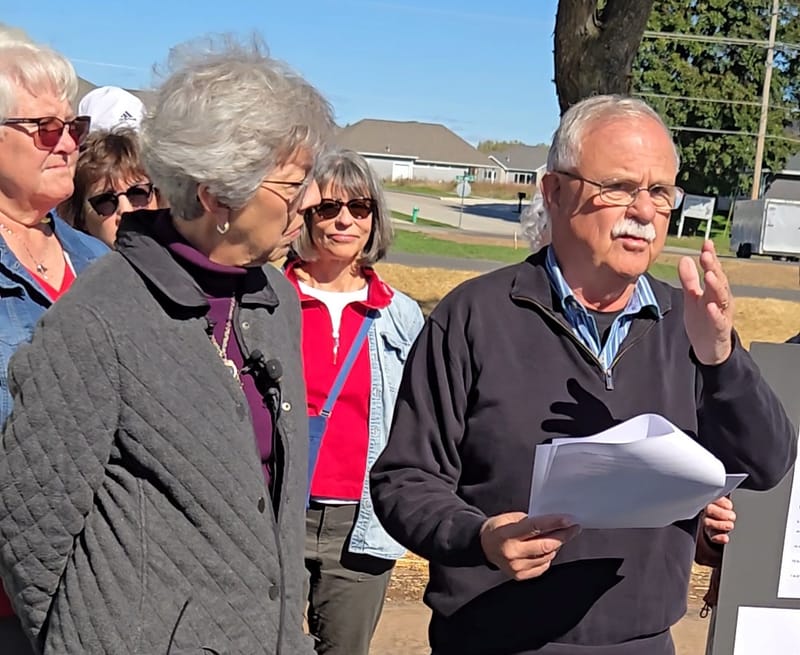

In the wake of procuring both items on his wish list from the Wisconsin state budget negotiations last week, Mike Pochowski was willing to defer for the moment the potentially dire ramifications of drastic cuts to the federal Medicaid program.

While the state biennial budget left a lot of people unhappy with both Republican legislators and Gov. Tony Evers, Pochowski, the President and CEO of the Wisconsin Assisted Living Association (WALA), was not among them.

“We’re definitely extremely happy with what the Joint Finance Committee and the governor voted on,” Pochowski said. “But from the federal standpoint, we’re still trying to go through that and figure out what that could mean for Wisconsin.”

What WALA got in those state budget negotiations were a continuation of the Family Care Rate Setting Initiative and the Direct Care Workforce Funding Initiative. The first sets a crucial minimum fee that assisted living facilities must receive while the second will go toward providing much-needed wage increases for long-term caregivers. In all the long-term care industry received $202 million in funding from the state.

Pochowski said the money should help avert – for now anyway – the possible closures of facilities or of facilities choosing to no longer participate in the Family Care program. Family Care is a state Medicaid waiver program for long-term care services in the state. Average hourly wages for caregivers will get a bump from $13.02 to $15.75 per hour.

“So it’s a huge increase, which is greatly appreciated,” Pochowski said. “But it’s still nowhere where it should be. For us to really effectively compete with other industries that typically hire the people we hire as caregivers – people in light industrial, retail, fast food and skilled nursing facilities – we really need to be in that $17-to-$20 range.”

Still so many challenges

Given that recent state budgets have been fairly austere despite the state holding on to a $4.3 billion surplus, there was no guarantee WALA would get what it did. So while Pochowski was breathing easier last week, the industry itself still faces significant headwinds, from President Trump’s mass deportations (immigrants make up a significant percentage of long-term caregivers) to a rapidly aging population that is sure to put more strains on an overburdened industry to low profit margins at lower-income facilities to Trump and the GOP cutting nearly $1 trillion in Medicaid in the budget bill earlier this month.

WALA and the industry must now reckon with all of that but, most immediately, the Medicaid cuts pose a potentially significant threat. A key question is, if the federal government cuts off some Medicaid funding to Wisconsin, will the state fill that gap?

“Yeah, I think that the concerns are that, if there are cuts to funding, if there are cuts to assisted living providers that participate in the Family Care program, that means you are going to have rate decreases at a time when wages and inflation continue to increase,” Pochowski said two days before those cuts were indeed passed by the US Senate. “So how do you make up that gap? From a provider standpoint, you probably, you probably can't. And so then that means that, unfortunately, you're probably going to see assisted living facilities close across the state because they're unable to continue to provide quality care and services to residents.

He went on, “Or, I think you could possibly see facilities just say, you know what, we're not going to participate in the Family Care program anymore and then that means there's a lack of accessibility for elderly individuals that are low income.”

Rural, low-income areas hit the hardest

The cost for a residence in a long-term care facility runs from $9,000 to $11,000 per month. Medicaid covers two of every three residents. There are nursing homes, which require a greater level of care; home care; and assisted living. These facilities derive their income from private pay, private insurance and Medicaid. Many take all three. Those facilities that are exclusively Medicaid-funded tend to have the lowest level of care because Medicaid reimburses only 82 cents of every dollar.

Long-term care is an industry that has long struggled, even before the recent cuts to Medicaid. Nearly 800 facilities closed over the past five years, while only 250 opened. A long-term care facility has little place to turn when the financial screws begin to tighten beyond what is bearable. They might reduce staff; they might limit the amount of time each patient receives; they might stop accepting Medicaid; they might go out of business.

Or the state itself might change its eligibility requirements as Medicaid dollars get stretched.

Rural and lower-income areas suffer the most when funding dries up.

“The facilities in the rural areas typically take the larger hits,” Pochowski said. “And from what we hear and from what we see, it's harder for them to recruit staff in those areas. And in the rural areas, you just see more providers are participating in the Family Care Medicaid waiver program so I think that if there are cuts from a Medicaid standpoint, from a federal level, you would probably see the rural areas get hit harder than the suburban or the urban areas.”

It won’t just be the Medicaid residents that suffer when a facility loses some of that funding but private pay and private insurance residents as well.

‘People are going to get sick and die’

Jason Sullivan-Halpern, director of the California Long Term Care Ombudsman Association, issued a blunt warning in a pbs.org interview in May, saying, “Let me be very clear: If these cuts happen … people are going to get sick and die.”

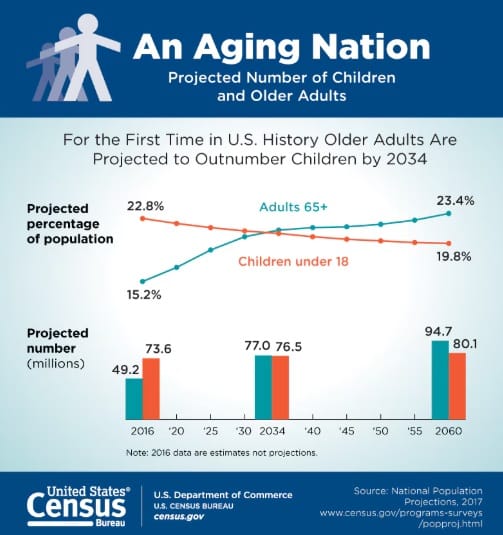

Pochowski remains grateful for the state coming through, though he said he’d also like to see inflation taken into account at budget time every two years when legislators are negotiating Family Care funding. He warns that our aging country needs to be prepared. Nearly one in four Americans will reach age 65 or beyond by 2060.

“And so you have more people getting older and we’ve termed that ‘the silver tsunami.’” Pochowski said. “And so we want to make sure that we have lots of programs, lots of accessibility, lots of facilities that are available to meet that need as it continues over the next several years. So if there's costs to Medicaid and if providers decide, you know what, we just can't do this anymore because the funding is not there, they exit the program, they shut their doors.

“Where are these elderly individuals going to go if there are fewer places that are offering these services? And so it's a huge concern, and honestly, I don't know what to do with that, except that we just need to make sure that the adequate funding is there for Medicaid.”

Long-term care gets state money but Medicaid cuts loom © 2025 by Kelly Fenton is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0